John Mahood & The Long Way Round

This article recounts the dramatic, traumatic, and tragic events leading to the first immigrant to California from the Gracia & Marchetti family. It is remarkable that one man’s life can be so thoroughly documented, placing him as, not only an eye witness, but a participant in historical events.

John MAHOOD was born 1825, son of Adam MAHOOD, in Magherally Parish near Banbridge, County Down, in Northern Ireland. The town of Banbridge was the centre of the ‘Linen Homelands’ owing its success to flax and the linen industry. Naturally, John became a weaver.

Into this pastoral setting arrived the Potato Famine 1845-1851 and County Down was hit hardest in 1847.

Ireland had witnessed a massive surge in population from 2.6 to 8.5 million by 1845 when blight struck the staple food of the masses – the potato. Two-fifths of the population were totally dependent on the potato and it was the major food-source of the rest. Between 1845 and 1849, the potato crop failed in three seasons out of four. The result was starvation and the spread of the “road disease” – dysentery, typhus and cholera.

It comes as no surprise in this climate, that John would enlist, age 22 years, with the Royal Artillery. Taking the Queen’s Shilling with the guarantee of three square meals would be attractive in such desperate times.

Gunner John Mahood rose through the ranks to Bomber, Corporal, and within seven years, attained the rank of Sergeant..

Sergeant John Mahood married Eliza Ann BUCK in 1855 in South Dublin, Ireland. Eliza Ann was an Ironmongers daughter from Saffron Walden in Essex, England. A daughter, Marguerite Martha Mahood, was born almost a year later, in Dublin.

Overseas service was inevitable. Leaving his wife and young daughter, John served 2 years and 7 months in China.

The Second Opium War (1856-1860) was fought over issues relating to the British export of opium and expanding access to Chinese markets, and resulted in a second defeat for the Qing dynasty.

The highly profitable opium trade for the British was severely detrimental to Chinese society. Levels of opium addiction grew so high that it began to affect the imperial troops and the official classes.

Panoramic view of the Allied encampment at the South Taku Forts, The Second Opium War, 1856-1860 © IWM (Q 69842)

Panoramic view of the Allied encampment at the South Taku Forts, The Second Opium War, 1856-1860 © IWM (Q 69842)The Royal Artillery was critical during the conflict but the heavy armaments had to be manhandled along narrow muddy trails as there was little infrastructure in 1850’s China. Pack horses were in short supply and the military did not trust that complex weaponry, disassembled and divided into individual portable components amongst the Chinese Coolies, could be re-assembled swiftly. The result was an arduous cross country trek for British troops hauling artillery pieces through rice paddies, and narrow hill trails, between battles.

The key 1857-1858 Battle of Canton (Guangzhou) followed a prolonged artillery bombardment of the city of 1,000,000 people. 5,000 British, Indian, & French troops scaled the walls quickly taking the city with the loss of less than 20 men. Hundreds of Chinese troops and civilians were killed and 30,000 homes razed to the ground.

In the aftermath of the battle and the occupation of the city of Canton, Sergeant John Mahood was court martialed in Hong Kong, jailed for seven days, and stripped of his rank, having been convicted of embezzlement. During the remainder of the China campaign John was promoted back to Bomber, but would have to wait until his return to England to receive re-promotion to Corporal.

Between postings, Corporal John Mahood was stationed at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, in London, and was preparing for a commission in British Guiana as a militia artillery instructor. Unfortunately Corporal Mahood’s travel was canceled due to illness and, within a month, was discharged from the Royal Artillery as unfit for service. Three good conduct badges and fourteen years under his belt.

No. 5125 Corporal John Mahood 4 Bn DB RA. This man suffers from mobility… Has been frequently operated upon, and is permanently disabled as a soldier. The actual ailment was induced of service in China, and not owing to new…

Woolwich, Aug 28, 1861.

After a careful examination, I am of opinion that John Mahood is unfit for Service and likely to be permanently disqualified for Military duty, but that he is able to earn a livelihood.

WCL Clement, Deputy Inspector Finance, P.M Offices

Horse Guards 9th Sept 1861.

Discharge of the Man above mentioned is approved by H.R.H. the General, Commanding in Chief

Although not specifically listed in the discharge papers, John was suffering from Elephantiasis, a debilitating and disfiguring disease. Obstructions in the lymphatic vessels resulted in enlargement and hardening of the lower limbs and body parts due to tissue swelling. The disease is transmitted by a parasite spread by mosquitoes and is still prevalent today in Africa and Southeast Asia.

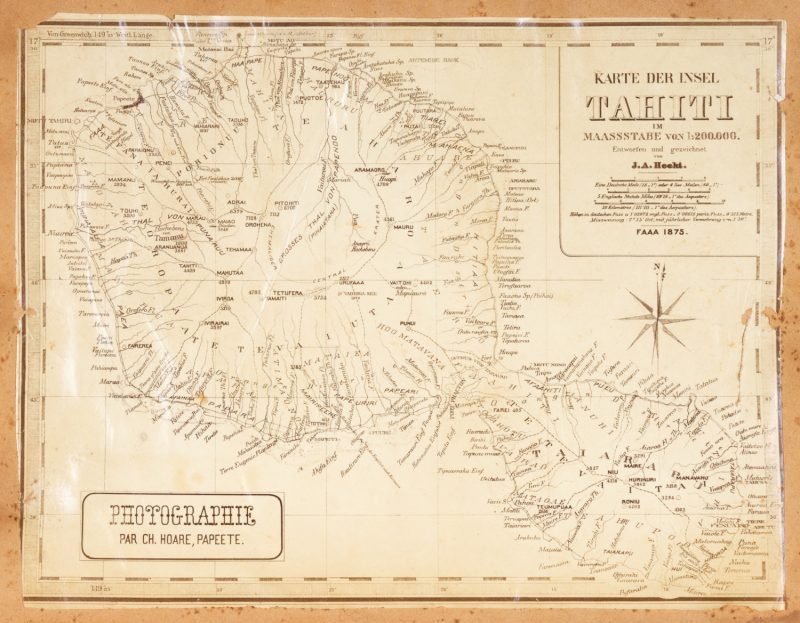

John & Eliza’s second child, Caduceus John William Mahood, arrived four months later in January 1862. We have no records for the family until four years later, when John is recruited by a French-Polynesian outfit in Tahiti, hiring former British non-commissioned officers as overseers of a cotton plantation. The Mahood family packed up their belongings, leaving Europe for the last time, to sail to Tahiti.

All was not as it seemed. Arriving with his wife, and children Maggie & Caduceus, for a five year contract in Tahiti, John Mahood declared… “When we arrived (Atimaono)… we were all obliged to go into debt. My bill came to $65.40.” … Before my bill was paid the manager discharged me by written notice dated August 23, 1866 … so that I never received any money on the plantation. On the contrary my bill shows me to be in debt.”

In 1863, British capitalist William Stewart set up the Tahiti Cotton and Coffee Plantation Company at Atimaono on the south-west coast of Tahiti. Initially Stewart used imported Chinese coolie labour but soon shifted to blackbirded Polynesian labour to work the plantation. These people were unloaded in a “half-naked and wholly starved” condition and on arrival at the plantation they were treated as slaves.

… John Mahood, a British subject, had been before the Correctional Court for punishment and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. The press abroad, particularly in the United States and Australia, began to publish sensational reports to the effect that Stewart had instituted a reign of terror, that the employees were cruelly treated, that corruption was rife in Government circles in Papeete. British overseers who refused to thrash the coolies and natives, it was stated, were themselves punished, and in the matter of correction Stewart held extraordinarily unjustifiable powers. One article headed “Tahitian Slavery” that appeared in a San Francisco journal aroused Stewart’s wrath, and he approached the Government for an official investigation.

William Stewart and the introduction of Chinese Labour in Tahiti, 1864–74. By Eric Ramsden.

Conditions at the Atimaono plantation were appalling with long hours, heavy labour, poor food and inadequate shelter being provided. Harsh punishment was meted out to those who did not work and sickness was prevalent. The mortality rate for one group of blackbirded labourers at Atimaono was around 80%, according to an article on Polynesian Slavery published in The Empire, Sydney.

For the second time in his life John Mahood was overseeing an imprisoned Chinese populace. It would be interesting to understand how his prior experience in Canton impacted his choices in Tahiti.

What is clear is that John Mahood disclosed a very different picture of conditions at Atimaono compared to those presented by plantation owner, William Stewart. When visitors were at the plantation, he said, the bell was rung at the correct time to cease labour, but only on such occasions. After finishing a long day’s work he was once ordered by Stewart to feed the horses. John demurred. The manager accused him of insolence, and ordered him to the “calaboose” for thirteen hours on bread and water. Rations for John and his wife were stopped. John was later sent 25 miles to Papeéte in the charge of a gendarme as a prisoner. He duly appeared before the court, was sentenced to gaol, and dismissed from the plantation.

Unfortunately for himself, John subsequently returned to Atimaono, was arrested on a trumped-up charge of allegedly inciting the Chinese, and was again lodged in prison. On his release John had to exist on what little work he could procure, also with what his wife could make as a seamstress. Stewart declined to furnish them with passages to England. In addition to the gaol term, John was subjected to a fine which increased steadily so long as he remained in prison. The fine was eventually paid by a friend. John returned the money from the meagre pension he received from the British Government. The original charge against him, incidentally, was “habitual idleness and neglect of work.”

INTELLIGENCE has reached us from San Francisco of the brutality to which coolies are subjected at Tahiti… His [William Poole] first duty was to oversee a gang of coolies in the cotton-gin shop. He found them all emaciated, and many suffering greatly from wounds, bruises, and loathsome ulcers. Still they worked patiently, and out of pity he neglected to urge them with the orange club which had been placed in his hand. The next day the manager came to him and complained that he had not beaten any of the people, and when he suggested that he had not found it necessary, the man fell into a towering rage, and threatened to take him before the tribunal of Papetee, an institution before which all the managers and bosses on the island may enforce their orders or their threats… A man named Mahood, of London, brother of a jeweller in Oxford-street, was the object of his tyranny, and was sent with scarcely a moment’s notice to the tribunal of Papetee, accompanied by his sick wife. There he was abused and nearly starved; they are there yet in a destitute condition. On one occasion Mahood drank some brandy in the hospital. He drank again, and was almost fatally poisoned ; and once he was sent to prison by the “Tribunal” for the term of one year, for some trivial offence.

Coolie Slavery in the Pacific, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 March 1870

Stewart realized, of course, that reports published in the foreign press were doing his enterprise considerable harm and proceeded to publish disparaging pamphlets dismissing the claims and attacking William Poole’s character after publication of the sensational claims in the San Francisco Times article “Cruelties of the Slave Trade in the Islands.” Poole declared that the scenes he had witnessed at Atimaono so horrified and disgusted him that he took the first opportunity of returning to California.

The labourers, numbering between 1,500 and 2,000, were slaves “in the most depraved and abject meaning of that term.” On the voyage to Tahiti they had been subjected to “scourge, starvation, and other brutalities,” in order to break their spirit, and so render them suitable for their employment. The outrages were perpetrated with the knowledge, if not with the consent of the French Governor. “If this be true,” the newspaper commented, “the subject is one worthy of protest from all the governments of the Christian world.

Poole stated that “irons, flogging, and dungeons” were the order of the day on the plantation, also that Stewart’s cruelties were not confined to Chinese and natives… pensioners from the English Army, were engaged in London under the most flattering inducements. They soon found … they were ‘sold.’ Their engagements were broken: they did not get enough provisions for themselves and their families without purchasing them, and their hard-won earnings went to keep their children from starving … One of the overseers named Mahood was dismissed for refusing to superintend the flogging of Chinamen. He applied to the British Consul, was told that he could do nothing for him as Mr. Stewart could do what he wished in Tahiti. He next sought justice from a French court but, poor man, he little knew what justice in Tahiti is! His case came on for trial—was immediately dismissed without himself being examined … he was ordered to pay the costs. He was thrown on his own resources, having an invalid wife and two children to support.” There is a ring of truth in that statement. Poole concluded by saying: “The English and American Consuls can do nothing to stop this tyranny. French steel is everywhere to support it … In short, the great Mr. Stewart, who claims to be a descendant of the Royal Stewarts of Scotland, is both civil and military Governor of Tahiti. He has but to command and the representatives of the Emperor Napoleon obey.”

William Stewart and the introduction of Chinese Labour in Tahiti, 1864–74. By Eric Ramsden.

By all accounts, noted above, the family was living destitute in Papeéte, surviving on John’s meager military pension, and Eliza’s work as a seamstress. In 1871, embroiled in this desperate situation, their 14 year old daughter, Marguerite, married a frenchman, Yves Paul Lequellec. Lequellec, a 32 year old cooper, had a shop in the Fare Ute district, re-purposing calvados (apple brandy) barrels and curing barrels.

The couple produce a son, Joseph John Teuria Lequellec in July 1872. Unfortunately the father missed the birth as he was traveling in France. We cannot be sure if Lequellec ever returned to see his wife and newborn son. Either way, John Mahood registered the birth as a child of a legitimate marriage, with witnesses, as noted in this certificate from the French Polynesian archives:

28 July 1872

Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia

Birth of Joseph, John, Teuira July 28, 1872 Act of birth ____ town of Papeete, 1872, 30th July, 2:00pm, Before us, BONNET Maximin, The Civil Status Officer of the Municipality of Papeete, Tahiti Island, centralized service for the States of the Protectorate.

In the common house … Mr John MAHOOD, age 45, no occupation, residing in Papeete rue Bonard, declared that his daughter Marguerite, Martha MAHOOD, no profession, gave birth on the 28th July, 7:00pm, in his house, a male child whose father, Yves, Paul LEQUELLEC, cooper, age of 33 years, ordinarily resident in this town, is currently absent from a trip to France. Declaring him appearing that this child was born from the legitimate marriage of the said Yves Paul LEQUELLEC and Marguerite Martha MAHOOD spouses and he gave him the first names of Joseph, John, Teuira.

The presentation and statement above were made in the presence of:

1st Mr Francois Felix TOUCAS, owner, age 53

2nd Mr Paul JOUANOU, restaurateur, age 41, both living in the municipality. Read to the witnesses and the declarant, they signed with us this Act. The notifier, Signed: John MAHOOD Witnesses Signed: TOUCAS F, S JOUANOU The Officer of the Civil Status, Signed: Mr. BONNET. P.C.C.C. The Registrar

William Stewart died in 1873 and the Tahiti Cotton and Coffee Plantation Company went bankrupt a year later. Coincidentally or subsequently, John requested an advance of £40 on his military pension to relocate his family to New Zealand but the British Army refused. However John was able to find passage to San Francisco, receiving his pension in the city from October 1873. It would take John over 10 months to afford the price of passage for his family to join him in San Francisco.

The shipping records are few and far between for journeys across the Pacific Ocean. Therefore, we are very lucky to have Eliza’s receipt of $180 for passage to San Francisco aboard the schooner, Maggie Johnson, with her two children and grandson.

(Record courtesy of Judith Gamba née Mahood)

In advance of their arrival in 1874, John & Eliza adopted their infant grandson as their own son and therefore arrived in San Francisco with three children: Marguerite 18 15, Caduceus 12, and Joseph 2. Marguerite’s date of birth was moved by three years, allowing her to enter the USA as a minor.

San Francisco was a bustling metropolis and a far cry from the colonial backwater of Papeéte. Check out this bird’s eye view of San Francisco in 1878 and Eadweard Muybridge’s panorama from the same year.

The family sourced accommodations on Dupont Street, now Grant Ave, the main street in Chinatown, which was actually San Francisco’s first street. This area used to be about a block from the bay, before land reclamation, and was essentially the first port of San Francisco. Chinatown was a rough place, with thousands of poor immigrants from southern China packed into miserable, unsanitary tenements.

John procured work as laborer, Eliza resumed her work as a seamstress, Marguerite, a dressmaker, and Caduceus became a clerk and telephone operator at the American District Telephone Company. Life was hard in San Francisco for John, attempting to support his family with intermittent labour jobs and long periods of unemployment, including 12 months up to the March 1880 census. We cannot begin to imagine the daily pain of living with an incurable, and disfiguring, illness alongside the limited benefits of the prescribed Quinine medication.

Commission of Insanity

John Mahood, an irishman, aged fifty-one, was also committed. He is dangerously violent and threatens his wife and children. It is thought the mental derangement is caused by the excessive use of quinine taken for a local disease. He has taken as much as thirty-two grains per day, for the last nine months.

23 March 1877, San Francisco Examiner

Quinine could have significant psychiatric effects, including causing depression, mania, irritability and personality change, and that these might not be distinguished from those attributed to disease, only relatively recently has it become clear that quinine may cause a serious toxic state marked by symptoms including delirium and confusion. Two week treatments of 5-15 grains per day was the average prescription, any more than 15 grains was considered toxic. John far exceeded his prescription.

John was sectioned a second, reported, time in December 1880 and committed to the Napa Asylum for the Insane. The hospital, when built, was the mental health facility for the entire Bay Area and was in the forefront of “occupational therapy” with its farms and workshops. According to many early accounts the hospital was entirely self-sufficient.

During John’s initial commitment, Marguerite, aged 18 years (actually 21), married another Frenchman, Francois GRACIA, and gave birth to a son Emile Vincent GRACIA in April 1877, although the order of these events is yet to be determined.

By 1883, the city directory lists John back in Chinatown, living on Bay Street with his wife and son, Caduceus, now an accomplished musician, while their adopted son, Joseph, was on the Honor Roll of Greenwich Street Primary School.

Britton & Rey’s Guide Map of the City of San Francisco, 1887

John Mahood passed away in 1885, aged 60, in his home on Bay Street, Chinatown. The cause of death was Elephantiasis, the disease with which he had suffered for twenty years.

John’s death was reported in the San Francisco Examiner & Chronicle, Sacramento Call & Record Union, Santa Cruz Sentinel, & Daily Alta California.

Following his death, John’s widow, Eliza Ann, lived on Valencia Street, in the Mission District, with sons, Joseph, carriage trimmer, and Caduceus, a musician. Once her sons married, Caduceus relocated to Oakland and Eliza Ann moved with Joseph and his spouse to the suburb of Glen Park, settling at 9 Surrey Street. Coincidently Marguerite and her family lived on the same block at No. 15.

Eliza Ann Mahood’s 88th Birthday 07 Aug 1911, Mon The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) Newspapers.com

Eliza Ann Mahood’s 88th Birthday 07 Aug 1911, Mon The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) Newspapers.com

In 1913, Eliza Ann outlived her adopted son Joseph, survived a serious bout of pneumonia, and celebrated her 90th birthday with friends and relatives at Marguerite’s home on Surrey Street. Eliza Ann Mahood passed away in 1915, age 91, in San Francisco.

Family Tree

- Adam MAHOOD (~1796-?)

- John MAHOOD (1825-1885) & Eliza Ann BUCK (1823-1915)

- Marguerite (Maggie) Martha MAHOOD (1856-1921) & Yves Paul Lequellec (1839-?)

- Joseph John Teuira Lequellec (1872-1913)

- Marguerite (Maggie) Martha MAHOOD (1856-1921) & Francois Pascale Gracia (1852-1930)

- Emile Vincent GRACIA (1877-1918) & Francesca Juana Medina MENDOZA (1876-1943)

- Joseph Emile GRACIA (1899-1987) & Claire Kathleen GRANT (1905-1989)

- Joan Shirley GRACIA (1929-2021) & Henry James Victor MARCHETTI (1928-2014)

- Our direct line…

- Gracia (living)

- Joan Shirley GRACIA (1929-2021) & Henry James Victor MARCHETTI (1928-2014)

- Frank John Gracia (1900-1944)

- Doris Mildred Gracia (1901-1988)

- Elsie E Gracia (1902-1996)

- Irene Edna Gracia (1903-1995)

- Mary Helen Gracia (1905-1905)

- Hazel Aurelia Gracia (1907-2007)

- Frances Gladys Gracia (1909-1950)

- Ernest Walter Gracia (1910-2002)

- Elena Gracia (1912-1998)

- Evelyne Cecelia Gracia (1914-2000)

- Ramon Gracia (1916-2010)

- Joseph Emile GRACIA (1899-1987) & Claire Kathleen GRANT (1905-1989)

- Mildred Cleo Gracia (1879-1949)

- Daisy Florence Gracia (1882-1886)

- Ernest Leo Gracia (1889-1962)

- Frank G Gracia (1891-1956)

- Firmin C Gracia (1897-1918)

- William E Gracia (1901-1978)

- Emile Vincent GRACIA (1877-1918) & Francesca Juana Medina MENDOZA (1876-1943)

- Caduceus John William Mahood (1862-1936)

- Marguerite (Maggie) Martha MAHOOD (1856-1921) & Yves Paul Lequellec (1839-?)

- John MAHOOD (1825-1885) & Eliza Ann BUCK (1823-1915)

References

- Magherally Parish, Wikipedia

- Irish Famine: How Ulster was devastated by its impact, BBC News

- Queen’s Shilling, Wikipedia

- Opium trade, British and Chinese history, Brittanica

- Battle of Canton (1857), Wikipedia

- Guangzhou (Canton), Wikipedia

- Elephantiasis, Wikipedia

- Pacific Islands trader James Lyle Young, DouglasStewart.com

- Polynesian Slavery, The Empire, Sydney, Trove

- Coolie Slavery in the Pacific, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 March 1870, Trove

- William Stewart and the introduction of Chinese Labour in Tahiti, 1864–74. By Eric Ramsden

- French Naval Frigate, L’Astrée, Wikipedia

- A. Crawford & Co. Chandlery and Ship Stores, San Francisco, Calif., between 1864 and 1892, garystockbridge617.getarchive.net

- A. Crawford Ship Chandlery Ship Store sail loft, San Francisco Circa 1880, Pixels.com

- Andrew Crawford 1828-1892, LoveAncestry.com

- Bird’s eye view of San Francisco, 1878 Historic Map Works

- Eadweard Muybridge’s panorama 1878, Wikimedia

- Commission of Insanity, John Mahood, The San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, California · Friday, March 23, 1877

- Psychiatric effects of malaria and anti-malarial drugs: historical and modern perspectives, National Library of Medicine

- Napa Asylum for the Insane, Wikipedia

- Britton & Rey’s Guide Map of the City of San Francisco, 1887, DavidRumsey.com

Updated John Mahood’s arrival in San Francisco prior to 1 October 1873 due to updated address for military pension, at least 10 months before his wife and children arrived. Also San Francisco was the fallback destination as the British Army refused an advance on his pension of £40 to move from Tahiti to New Zealand.

Updated Sergeant John Mahood’s court martial details for embezzlement, seven days in jail, and rank reduced to Gunner!

The shipping company which delivered Mrs Mahood and children to San Francisco was most likely A. Crawford & Co. Chandlery and Ship Stores, San Francisco, CA: https://garystockbridge617.getarchive.net/amp/media/a-crawford-and-co-chandlery-and-ship-stores-san-francisco-calif-between-1864-538d06